A Family History

The work we do at the Banyan Tree to raise the next generation of South Asian youth has a long history. It is the history of our parents, our grandparents, and the 7 generations before us who imagined a better future, knowing they may not live to witness it in their lifetime. We stand on their shoulders, so the next generation can stand on ours. I want to share the story of my grandfather, whose shoulders I stand on.

My grandfather was born in an agricultural family in coastal Andhra Pradesh. In this village along a stream that flowed from the Krishna river, stood a shrine to a Sufi saint named Saidulu. So when my grandfather was born, his parents named Saidulu. Saidulu is the Telugu pronunciation of the common name, Said. In the diverse religious landscape of coastal Andhra, a Hindu child carrying a Muslim saint's blessing was beautifully unremarkable.

Photograph by Saidulu Kola

A dargah in coastal Andhra photographed by my grandfather. It is likely the dargah of the Sufi saint he was named after.

In the 1940s, my grandfather was a teenager, and a fervor was taking hold of his sleepy town. The independence movement had reached the agricultural heartland, and here it wore a distinctly Marxist face. The peasant organizers of Andhra weren't just fighting the British. The young Marxists of Andhra dreamed of a world where farmers could live and thrive, a world without caste violence, religious violence, or discrimination – a world of peace and equality. The India they imagined wasn't just free; it was fair. For young Saidulu, like for many young people, the call of justice was irresistible.

He decided to follow Gandhi's strategy for pushing the British out: flood the jails, fill the streets, and make the country ungovernable through the sheer presence of peaceful masses of human bodies. Saidulu put his body on the line, and he often ended up in jail. (In fact, he got set up with my grandmother while in jail, but that’s a story for another time.)

Not every non-violent protest stayed non-violent. The police would charge with lathis (long sticks) and the protestors would take their beatings without moving. Sometimes the crowds surged, the officers panicked, and the lathi charge became gunfire. The soldiers usually aimed high, over the heads of the crowd.

Usually.

One day, 16-year-old Saidulu was at a non-violent protest, when the bullets started flying. He ran for his life, along with the rest of the protestors. A man fell on his left and died. Another fell on his right. And then, as he was running, a third body dropped from the tree above him. A spectator who had climbed the tree to watch the protest had been hit by a bullet. Later, he would ask himself the question that survivors often ask: Why did I get to survive when they didn’t?

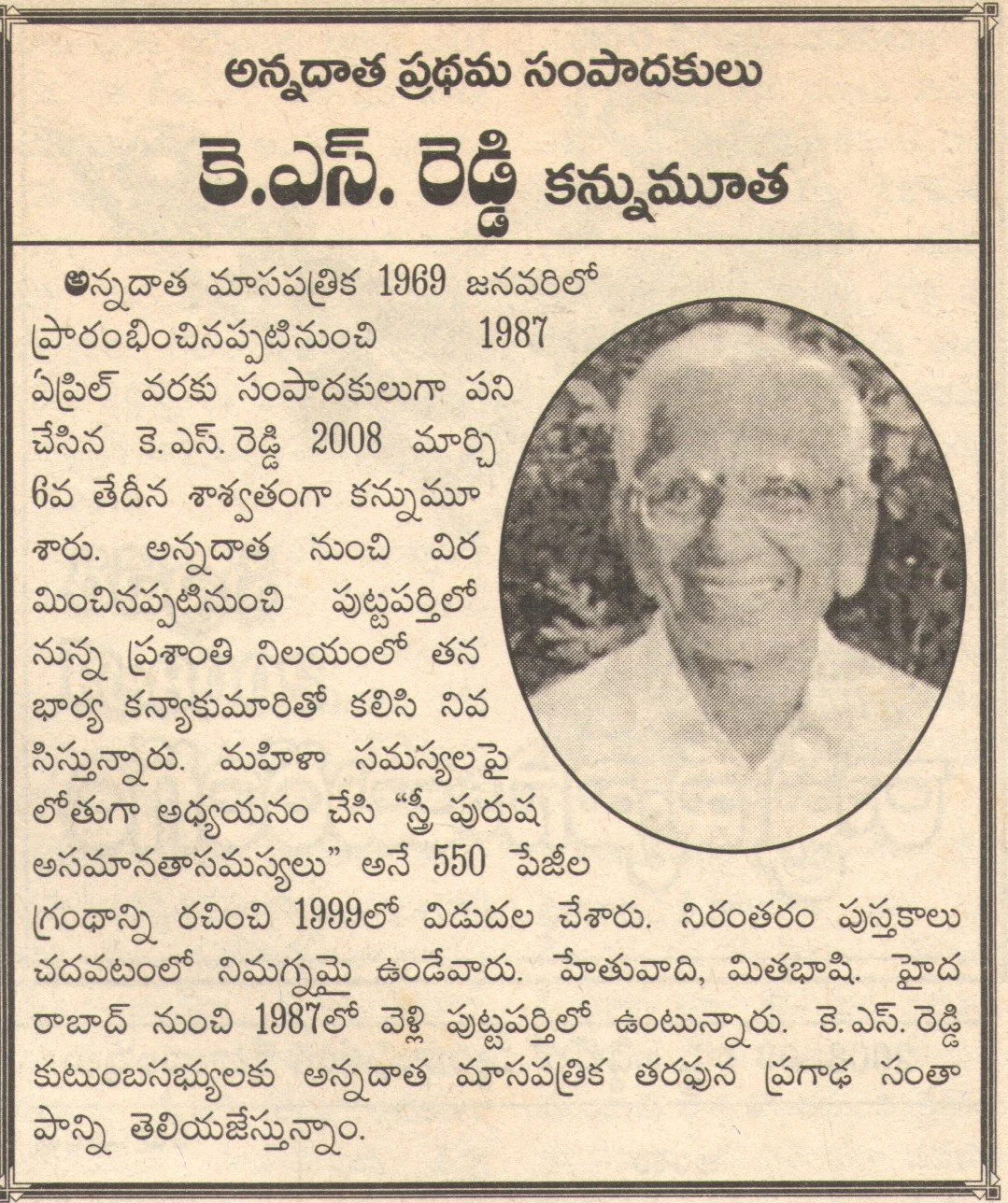

Clipping from Annadata about Saidulu Kola

The Telugu language monthly for farmers in Andhra where my grandfather worked as the editor since its inception. It is the most widely circulated monthly magazine in India as of 2019.

After the independence movement, he dedicated his life to the farming world he grew up in. He left his village to go to Hyderabad and become an agricultural journalist. Though he dreamed of going to college to better serve his agricultural community, he had to forgo this dream due to his extended participation in the freedom struggle as a young man. With extensive reading and raw determination, he pulled himself up and started a Telugu magazine to bring critical information to farmers. He ultimately wrote over ten books in Telugu.

On the 25th Anniversary of Indian Independence, the Indian government offered Saidulu a plaque and a small pension honoring his imprisonment during the freedom struggle. He refused it, because the India whose freedom he had fought for – the one free of caste, regional, and religious animosity – hadn't yet arrived.

Towards the end of his life, he saw the arrival of new reforms and improved living conditions for more people. Though it was very delayed, it was rewarding for him to see the dreams he had as a teenage boy slowly, bit by bit, partially, come to life.

Saidulu Kola died peacefully in his 80s, still waiting for the equitable India of his dreams to be realized, but with hope that it could happen. I hope through the Banyan Tree, we can take one step towards the world that he and so many others have dreamed of for centuries: a world where the preciousness of each human life is cherished and valued. A world of peace and equality.

Saidulu & Kanyakumari Kola

My grandfather and grandmother in their last home, surrounded by their Telugu books.