Brown Skin, White Masks

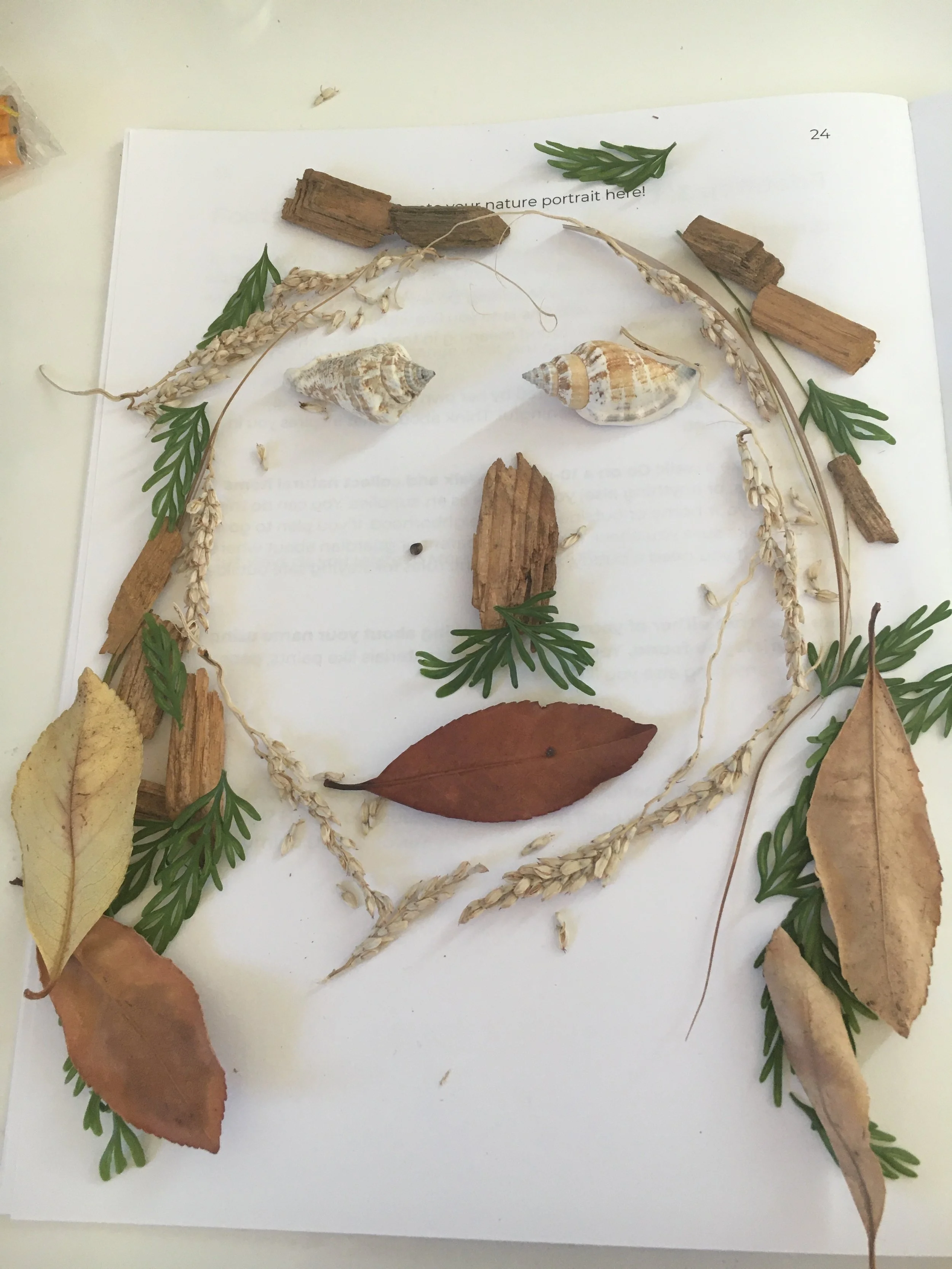

Self-portrait by Ayesha (12 years old)

When children first arrive at The Banyan Tree and we ask them to draw themselves, something striking often happens: they reach for the peach crayon. Even children from affirming homes, surrounded by family members who celebrate their heritage and beauty, render themselves pale—sometimes white—on the page.

This is a reflection of the visual world children swim in every day: picture books, advertisements, animated characters, the default "skin color" in every crayon box. The message is subtle but persistent—whiteness is the norm, and everything else is a deviation from it.

We're not the first to notice this phenomenon. In the 1940s, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark conducted their famous "doll experiments," presenting Black children with identical dolls differing only in skin color. When asked which doll was "nice" or "pretty," the majority chose the white doll. When asked which doll looked like them, they pointed to the Black doll—often with reluctance or distress. This research became pivotal evidence in Brown v. Board of Education, demonstrating the psychological damage of segregation. But the pattern persists. Studies continue to show that children of color, as young as preschool age, often associate lighter skin with positive attributes and darker skin with negative ones—a bias absorbed from a culture that still centers whiteness as the aesthetic ideal.

At The Banyan Tree, we believe the antidote isn't a single conversation but a gradual practice of looking—really looking—at ourselves and each other. Our self-portrait curriculum unfolds slowly, building comfort and skill before asking children to render themselves realistically.

We begin with abstraction: self-portraits made from natural materials like leaves and seeds, where representation gives way to texture and symbol. Then come blind contour drawings, where children trace the outline of their own hands without looking at the page. The results are wobbly, imperfect, and often hilarious—which is exactly the point. We want to release the grip of perfectionism before precision matters.

Only then do we move toward realism. Children learn to mix colors—really mix them—to find the exact shade of their own skin. Not "tan" or "brown" from a pre-labeled set, but a color they create themselves, that belongs only to them.

We collaborated with artist Jinjin Sun, whose "100 Days" project placed her own image into masterworks of Western art, claiming space in a canon that historically excluded faces like hers. Jinjin worked with our students to create self-portraits that don't just depict them accurately—but depict them confidently. The portrait featured here emerged from that collaboration: a young person rendered in warm earth tones, framed by leaves, meeting our gaze directly.

The title "Brown Skin, White Masks" borrows from Frantz Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks, his searing 1952 analysis of how colonized people internalize the colonizer's gaze, learning to see themselves through eyes that diminish them. For South Asian children, this internalization carries layered histories. Colorism in South Asia long predates European colonialism. Dark skin was associated with laboring under the sun, with Dalit and Adivasi communities, with caste positions deemed "lower." These stigmatizing associations that harmed Dalit and Adivasi communities also coexisted with contradictory currents. In the Mahabharata, Draupadi—celebrated as the most beautiful woman of her age—is called Krishnaa, "the dark one," her skin likened to the fragrance of a blue lotus. The hero Arjuna, too, bore the name Krishna, given by his father "out of affection towards his black-skinned boy." Folk poetry describes the god Krishna as ghana-shyam, dark as monsoon clouds heavy with rain—and in a land dependent on those rains, there was no image more beautiful or life-giving. Beauty standards were not monolithic. Admiration and stigma existed simultaneously.

Colonialism flattened this complexity. British rule injected language and experiences into India that amplified the association between darkness and inferiority, lightness and power—while suppressing the celebratory associations with darkness. The fairness cream advertisement and the auntie's warning to stay out of the sun carry forward this colonial inheritance, but they also echo older structures of caste and class. When a child reaches for the peach crayon, they are responding to all of this at once: the weight of Western media, the echoes of caste hierarchy, the flattened post-colonial world where dark simply equals less-than. To counter this, is not simple. At The Banyan Tree, we try to help children see the full picture through historical analysis of beauty advertisements.

An example of some of the beauty ads from different periods and places we put side by side to have kids analyze the long, global history of colorism.

In the process, they discover that the erasure of dark skin as beautiful is not an ancient truth but a historical wound. And wounds can heal, one brushstroke at a time.

A self-portrait is never just a picture. It's a statement: I see myself. I am worth seeing. And when children learn to see themselves clearly, they begin to imagine a world that sees them too.